The Growing Spread Between WTI and Brent Crude Oil: What Does it Mean?

Investors should heed the price spread between West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent crude oil. The oil prices you read about in the newspaper and hear about on television often refer to WTI, the variety of crude oil that underlies futures contracts traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange. WTI typically reflects supply and demand conditions in the

For many years, the differences between the two classifications were negligible. As the world’s largest oil consumer,

Brent crude oil traditionally trades at a $1 to $2 discount to WTI because it’s of slightly inferior quality. But regional supply and demand conditions can throw off this balance. For example, in 2005 WTI traded at a larger-than-average premium to Brent because of hurricane-related supply disruptions on the

This familiar relationship between WTI and Brent crude oil has unraveled once again.

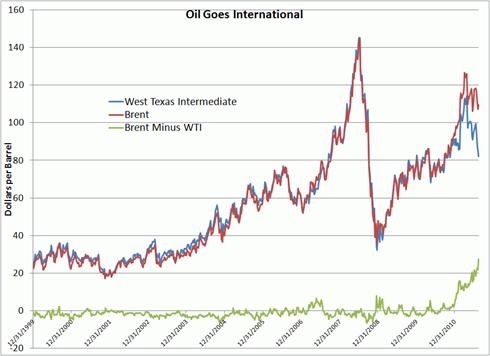

Source: Bloomberg

Although both oil benchmarks have pulled back from their 2011 highs, WTI has taken a much bigger hit than its European counterpart. Whereas the price of WTI has tumbled roughly 28 percent from its high in late April to its recent low of about $82 per barrel, Brent crude oil has declined by only 15 percent from its high of almost $127 per barrel to its recent low of $107 per barrel.

Meanwhile, Brent has commanded premiums of as high as $30 per barrel in recent trading sessions.

Despite its increasing irrelevance to the global oil market, WTI remains the most widely quoted oil benchmark in the

As

This shift has not only glutted storage facilities at Cushing, but reversed pipelines have also limited flows out of the hub. When an influx of crude oil overwhelms refining capacity, stockpiles build, and the price of WTI declines. This logistical logjam can only be resolved by the construction of new pipelines to move crude oil from Cushing to the

Light, sweet crude oils trade at Brent-like prices on the

A few companies that have proposed projects to develop oil pipelines to connect Cushing to the Gulf Coast, including Proven Reserves Portfolio bellwether Enterprise Products Partners LP (NYSE: EPD). The master limited partnership (MLP) recently announced the termination of joint venture with Energy Transfer Partners LP (NYSE: ETP) to develop such a project. But management also indicated that it remains committed to the project and will continue to solicit commitments from shippers.

Even if one of these proposed pipelines gets the go-ahead and comes on-stream, there won’t be enough new capacity to alleviate the glut at Cushing.

Demand conditions haven’t helped matters. As WTI prices tend to reflect the

Meanwhile, Brent crude oil’s strength reflects a much tighter supply and demand balance for crude oil outside the

You can’t analyze the global oil market by parsing weekly changes in US inventories; rising oil consumption in

Despite ongoing weakness in the

With the

Whereas developed-world oil demand declined from 2000 to 2010, oil consumption in countries outside the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has soared by 12.5 million barrels per day. Chinese oil demand has roughly doubled in 10 years. In 2000 the country’s oil consumption represented roughly a quarter of

Meanwhile,

These demand trends are reflected in the widening gap between WTI and Brent crude oil. Key emerging economies also show no signs of slowing.

While US policymakers and their counterparts across the pond look for ways to pep up their lackluster economies through unconventional monetary and fiscal policies, emerging markets such as China and

Economic growth in

For example, HSBC (LSE: HSBA, NYSE: HBC) publishes a “Flash PMI” number before the official release. This flash PMI number jumped from 48.9 to 49.8, a far larger increase than most economists had expected.

Meanwhile, the advance estimate of the MNI Business Sentiment Index indicated that new orders jumped 3.39 percent during the August reporting period, up from a 3.02 percent increase in July and a contraction of minus 3.89 percent in June. The advance report also showed improvement in index’s production component.

Bottom line: The Chinese economy continues to perform well and has picked up modestly after a policy-induced slowdown. Moreover, credit troubles and concerns about looming recession in developed countries should reduce pressure on emerging markets to tighten their monetary policies. A positive outlook for the Chinese economy has also supported Brent crude oil prices.

According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) latest Oil Market Report, global oil demand is expected to reach 89.5 million barrels per day in 2011, up 1.2 million barrels per day from 2010. The IEA forecasts that oil demand in 2012 will grow by 1.6 million barrels per day to 91.1 million barrels per day. To put this into perspective, global oil demand amounted to 70 million barrels per day in 1995.

The IEA report forecasts a decline in US and EU oil demand in 2011 and 2012, which prompted the agency to scale back its estimate of consumption growth. Nevertheless, Asia, Latin America and the

At the same time, the IEA’s lower oil demand forecast pales in comparison to the downward revisions made to its oil production estimates. At the beginning of 2011, the agency projected non-OPEC oil production growth of 600,000 barrels per day in 201; the IEA’s latest report reduces this estimate to roughly 400,000 barrels per day.

Of course, the loss of Libya’s 1.5 million barrels per day of oil exports has shifted the focus to OPEC production.

With opposition forces rolling into

But investors need to be skeptical of any claims that “This time it’s different.” All the talk of a quick restoration of Libyan oil production is eerily reminiscent of predictions that Iraqi oil production would quickly recover and swamp global oil markets with excess supply. Iraqi oil production continues to increase, but early predictions about the country’s output have proved hopelessly optimistic.

If the

Finally, investors’ general failure to appreciate the durability of the Brent to WTI price gap has unduly punished shares of some of our favorite growth stocks. With Brent oil prices well above $100 per barrel and unlikely to fall below $95 per barrel, international oil and gas producers will continue to spend on new oil production projects.

Solid second-quarter earnings and an uptick in international markets haven’t spared the group from the carnage in the broad market. Panicked investors have also overlooked the relative resilience of Brent crude oil prices in this fraught environment.

Some of this weakness is a function of investor conditioning. When the outlook for global growth dims, investors sell higher-beta names first. The Philadelphia Stock Exchange’s Oil Services Index has exhibited a beta of 1.40 over the past five years; the S&P 500 Energy Index, on the other hand, has a beta of 1.07 over the same period. A beta of 1.0 indicates that a particular sector tends to move at about the same speed and in the same direction as the S&P 500 as a whole. Betas of greater than 1.0 imply more volatility and less than 1.0 suggest less volatility.

If the S&P 500 breaches its technical support near 1,100 or 1,120, expect services names to give up more ground. But these stocks appear extraordinarily cheap. For example, shares of Schlumberger (NYSE: SLB)–an industry leader with a flawless–currently trade at 3.23 times book value and less than 20 times forward earnings estimates. The stock traded at similar valuations from late 2008 to early 2009, a period when global spending on oil and gas production ground to a standstill and Brent crude went for $40 to $65 per barrel.

You can see my SeekingAlpha.com article, Oil Services: Ready to Serve Up Profits, and

Stock Talk

Add New Comments

You must be logged in to post to Stock Talk OR create an account